Shoulder Muscles: How to Improve Function and Avoid Pain

Broad, defined shoulder muscles are like a billboard declaring, “I WORK OUT! But if you don’t take care of this complicated joint, that little sign can quickly turn into “ROAD CLOSED!”

As many as two-thirds of people will experience shoulder problems during their lifetime, according to a Dutch research review. Even more startling: When researchers at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center performed MRIs on people who reported no complaints of shoulder pain, they discovered that 82 percent of the adults tested showed signs of arthritis in the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. (That’s the bump on top of your shoulder where your shoulder blade and collarbone meet.)

All the more reason to know how the shoulder muscles tasked with supporting this vital joint are supposed to function.

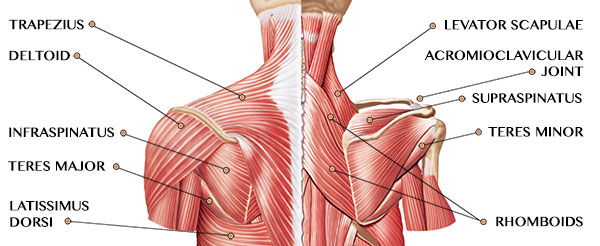

Shoulder Anatomy

There are four main joints within the shoulder complex, and an even greater number of muscles involved in moving both the humerus (upper arm) and scapula (shoulder blade). We’re going to focus on the two primary joints associated with major movements.

GLENOHUMERAL JOINT

This is the technical name for what most people consider the shoulder joint. This is where the humerus attaches to the scapula to form the most mobile joint in the body.

Thanks to its many surrounding muscles, the glenohumeral joint flexes (raising in front of you), extends (bringing behind you), adducts (pulling across your body), abducts (raising out to the side), and internally and externally rotates your arm. Then it does something funky called circumduction, a combination of those first four movements that results in a windmill type of motion.

All of that mobility, however, comes at the cost of stability. Exhibit A: baseball pitchers, who have among the highest rates of shoulder injuries.

Deltoid muscle

Function: Flexion (anterior head), abduction (lateral head), and extension (posterior head) of the humerus.

You’re probably very familiar with this first shoulder muscle, the deltoids, or “delts.” A triple-headed muscle (anterior/front, lateral/side, and posterior/rear) that forms the “cap” on the shoulder, the delts each originate at different points along the scapula or collarbone, and come together nearly halfway down the outer side of your humerus.

Rotator cuff muscles

Function: Stabilize the shoulder and help with adduction, abduction, and rotation of the humerus.

The muscles of the rotator cuff lie beneath the delts, cradling the shoulder end of the humerus like a pair of Spanx. The acronym S.I.T.S. may help you remember them:

- Supraspinatus runs along the top of your shoulder blade and helps raise your arm out to the side.

- Infraspinatus and

- Teres minor both cover the back of your shoulder blade and externally rotate your arm.

- Subscapularis runs along the anterior surface of the shoulder blade — the part that faces your ribcage — and helps with internal rotation and adduction.

The location of the S.I.T.S. muscles (around the shoulder joint) increases the risk of impingement, which happens when they become pinched between the humerus and the scapula, usually as a result of repeated overhead movements. “Rotator cuff injuries are more common than deltoid injuries, but a strength imbalance between the deltoids and rotator cuff muscles can increase the risk of impingement as well,” says Trevor Thieme, C.S.C.S.

These small shoulder muscles and their accompanying tendons are also at risk of tearing — especially if they’re weak — when you subject your shoulder to extreme ranges of motion and/or repetitive movement. That’s why it’s important not to neglect any part of your shoulder during training.

Other muscles supporting the glenohumeral joint

The latissimus dorsi (“lat”) and pectoralis major muscles also help control motion at the shoulder.

- The latissimus dorsi, which is among the body’s largest muscles, originates near the spine and wraps under the arm, attaching at the front of the humerus. It helps adduct, extend, and internally rotate the arm. (Assisting the latissimus dorsi is the teres major, which runs from the scapula to the humerus.)

- Pec major helps adduct, flex, and internally rotate your arm. It originates along the collarbone, sternum, and upper part of the rib cage, and attaches to the front of your humerus.

If you haven’t been counting, we’re already at seven shoulder muscles that attach to the humerus and help it move. And we haven’t even gotten to shoulder blade function yet.

SCAPULOTHORACIC JOINT

The scapula connects to the humerus at the glenohumeral joint, but it also utilizes a whole different set of shoulder muscles for its own movement and stabilization. This movement centers on the scapulothoracic joint, which, while not a joint in the traditional sense, allows for the shoulder blade to glide along the posterior ribcage.

Scapular muscles

Muscles associated with the scapulothoracic joint include:

- Pectoralis minor, which lies underneath the pec major and helps protract (pull forward) the scapula.

- Levator scapulae, which connects your neck to your shoulder blade for the purposes of elevation.

- Trapezius (aka “traps”), which originates at the center of your back and fans upward to the neck and shoulders to elevate, retract (pull back), and depress the scapula.

- Serratus anterior, which consists of fingerlike muscles that grip the sides of your ribs. Also called the “boxer’s muscle,” because it helps protract the scapula when throwing a punch.

- Rhomboids, which are located underneath the traps, and help elevate and retract the scapula.

If you sit in front of a computer all day and/or are stressed, it’s likely these shoulder muscles are imbalanced, which leads to muscle tension and pain. Your upper traps, levator scapulae, and pec minor — which draw the shoulder blade forward and upward — are probably overactive, creating that hunched, rounded-shoulders look. Meanwhile, your rhomboids, middle and lower traps, and serratus anterior — which draw the scapula down toward the ribcage — are probably underactive.

Now you can see why the shoulders are often so challenging; so many muscles, not a ton of space for tendons to slide around, a variety of movements (many of which can be repetitive), and it’s all being utilized even when you’re just sitting at your desk.

Besides potential arthritis in the joint, many people experience shoulder pain around the top of the arm, near that bony part of the shoulder. Called subacromial pain syndrome (S.A.P.S.), it has many potential causes, but it often derives from impingement of the tendons in that area, weak rotator cuff muscles, and poor shoulder blade biomechanics. Problems associated with S.A.P.S. include bursitis, rotator cuff tears, and biceps tendinitis.

4 Training Tips to Avoid Shoulder Problems

You’re probably not pitching too many fastballs, but regular exercisers can get into trouble with their shoulder muscles and connective tissues all the same. A 2011 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research compared two groups of women, one that trained with weights and one that had no experience with resistance. Researchers found that the workout group had less range of motion and greater shoulder instability in certain directions than the non-strength bunch.

“People who weight train have more shoulder pain than the general population,” says study co-author Morey J. Kolber, P.T., PhD, a professor of physical therapy at Nova Southeastern University in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. “These muscle imbalances contribute to pain and injuries, but they are easily preventable.”

Here are four things you can do today to ensure shoulder integrity:

1. Avoid overextending the front of your shoulder

Exercises that involve putting your arms in the high-five or goalpost position — like during the behind-the-head lat pulldown or the overhead press with flared elbows — can stretch the joint capsule and ligaments of the shoulder. That can lead to instability, says Kolber. “You’re putting your shoulder in a vulnerable position, so avoid that motion.”

2. Don’t ignore your rotator cuff

Moves that target the S.I.T.S. muscles, especially external rotators the infraspinatus and teres minor, help strengthen these stabilizers. A recent study of people with S.A.P.S. published in The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy found that doing eccentric external rotation exercises — focusing on the phase of the move in which the target muscle lengthens (e.g., the lowering phase of a biceps curl) — helped improve strength, pain, and function more than a normal shoulder exercise program.

Try this external rotation exercise:

- Anchor the end of a resistance band to a sturdy object, and stand perpendicular to the anchor point, holding the other end of the band in your right hand.

- With your right elbow bent at your side 90 degrees, hold the band in front of your abs, and step away from the anchor until there’s no slack in the band.

- Use your left hand to push your right hand out to your right side (taking away the work of the concentric phase of the movement).

- Release your right hand, and slowly return to the starting position, resisting the pull of the band. Do 2 sets of 15 reps per side.

3. Balance out your exercises

Ideally, you want to maintain a similar amount of strength and flexibility on both the front and back of your body, says Kolber. In order to do so, he recommends performing an equal number of pushing and pulling movements.

“The posterior [rear] heads of the deltoids tend to be under-trained, because people can’t see them and they don’t know how to target them,” says Thieme. “As a result, the posterior head tends to lag behind the other two heads on most people.” Pull-ups, cable reverse flys, and bent-over lateral raises are effective ways to work this important muscle.

4. Don’t overwork your traps

Men in particular love to do shrugs to target their upper traps, which originate at the back of your head and spine, and run along the tops of your shoulders. But these muscles are often already overdeveloped, thanks to stress and poor posture.

The tighter your traps are, the more they’ll pull on your neck and shoulder blades, causing strain that can turn into pain. Instead, target the middle and lower traps (pull-ups are a great option here, too), which help draw the shoulder blades down.